Turkish and Modern Greek have language games like English’s Pig Latin. These two languages’ games are syllable based like Pig Latin and show signs of being related to each other. For example, Modern Greek’s game is called Korakistika, which translates to ‘Language of Blackbirds.’ Likewise, the Turkish game is called Ķus Dili which literally means ‘Bird Language.’ Barıs Kabak, “Hiatus Resolution in Turkish: an Under Specification Account,” Lingua (2006) 15. Besides the similarities in these two names the game rules are almost exact duplicates. Language games offer some pretty valuable opportunities to explore the grammatical rules languages have.

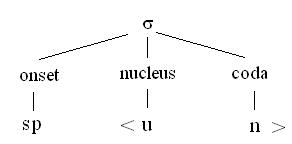

The rules of English’s Pig Latin should be familiar to most readers: in Pig Latin the initial onset of a word is placed at the end of the word and a vowel (it sounds like ay as in hay) is added to the end. (Technically that vowel is a dipthong and is represented by /eɪ/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet). If there is no onset then only that diphthong is added at the end of the word. So for example, let’s take the word ‘spoon,’ which happens to be just one syllable. There is an onset cluster of /sp/ followed by a nucleus and a coda. Below /σ/ stands for ‘syllable.’

Okay, for something simple like Pig Latin that sounds pretty complicated right? So what does all that mean? The ‘morphological operation’ we’re dealing with in Pig Latin is adding the sound /eɪ/. But that operation only applies to part of the word, which in our case is/sp/. So here is the prosodic circumscription taking place:

Next, a new syllable is formed by adding the diphthong /eɪ/ to the original onset:

So /sp/ served as the base for the morphological operation. And finally, this new syllable is added to the originally circumscribed post-onset parts of the word.

We started with the one syllable word [spun], and, in this way, the new Pig Latin two syllable word [unspeɪ] is formed.

But everyone already knows how to play Pig Latin — big deal right? Well… sometimes these rules aren’t followed, and that’s where things can get interesting from a linguistic point of view.

In Pig Latin we can see dialects occur among those who play the game. Differences in word creation arise when the original word has a consonant heavy onset such as /s-consonant-(consonant)/ sequences, that is sequences like /str/ or /sp/, as in words like ‘spoon’ or ‘strike.’ In one study two dialects were identified. Jessica A. Barlow, “Individual Differences in the Production of Initial Consonant Sequences in Pig Latin,” Lingua (2001) 673.

First we have Dialect A, where initial consonant clusters are divided and only the initial consonant is moved to the end of the word — so ‘strike’ becomes ‘trikesay’ and ‘spoon’ ‘poonsay.’ And second, we have Dialect B, which obeys conventional Pig-Latin rules — ‘ikestray’ and ‘oonspay.’ The study found 80% of people prefer Dialect B when they play Pig Latin. Id. at 674.

We also see people divide the initial consonant cluster when we have a /consonant-j/ sequence in words like ‘cute’ [cjut] or ‘few’ [fju] (in the IPA /j/ is pronounced like English /y/ — so we have ‘cyute’ and ‘fyu’). It’s not really certain whether the /j/ should be attached to the nucleus of the syllable, forming a diphthong, or if it belongs to the consonant cluster and should be moved to the back. “[B]ecause of their unusual patterning in English, /s/C(C) and C/j/ sequences are assumed by many to differ from other consonant sequences in their subsyllabic structural representation; that is, they may not comprise a ‘consonant cluster’ [. . .] but rather some other type of structure.” Id. at 669.

From the word ‘cute’ Dialect A gives [jutkeɪ] and Dialect B, which obeys the standard rules, curiously yields [utkeɪ]. Id. at 670.

This is weird because we would expect [utkjeɪ] from Dialect B.

So what is going on? Well, this is indeed what is formed by the rules, but only as an underlying representation. The actual output, [utkeɪ], is the surface representation which conforms to English ‘syllabic phonotactic constraints.’ Id. at 670. This is because the consonant cluster /kj/ can only be followed by /u/ in English, and so the /j/ gets deleted. Id. at 668. So, English phonotactic constraint rules are being applied after the application of the Pig Latin rules. This basically means English is not okay with allowing a syllable that sounds something like ‘kyay’ or [kjeɪ].

So that’s Pig Latin, and the insights into linguistics we can gain from studying it are pretty cool. Now let’s turn to the Greek language game, Korakistika. This game uses prosodic circumscription, but it uses a simpler process than Pig Latin. Where Pig Latin’s rules are applied once per word, Korakistika’s are applied once per syllable.

Let’s look at an example. We have a Greek sentence roughly transliterated as ‘ho daskelos erchetai’ but under the IPA as [ho daskәlos әrχәtai] — and in Greek ‘ο δασκαλος ερχεται’. This sentence means ‘the teacher is coming.’ Under the game rules, it becomes ‘hoko dakaskakalokos ekercheketaikai’ or [hoko dakaskakalokos εkәrχәkәtaikai](‘οκο δακασκακαλοκος εκερχεκεταικαι’).

This looks pretty daunting at first glance, but the process is really simple.

The first word in the sentence [ho] is just an onset and a nucleus. The game rules need only a nucleus, so there may or may not be an onset. With no coda there is only reduplication and addition of the entire syllable to the base, but during the reduplication the onset is just changed to /k/ or if there is no onset present then /k/ is added. So, we have:

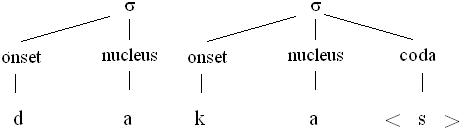

The process gets a little more complicated if we have a coda. In those cases prosodic circumscription becomes necessary. So let’s look at the next word of the sentence, which has a coda in the first syllable:

The first syllable’s coda has to be circumscribed before the reduplication process takes place:

After the reduplicated new syllable is added to the end of the first one — the circumscribed coda is finally added to the very end of everything.

The next syllable is basic enough and reduplicates with no change since the onset was originally a /k/.

Finally, the last syllable is treated a lot like the first. The coda is circumscribed and added after all the other processes:

So, when the entire process is complete we have a new, lengthy word left: from [daskәlos] to [dakaskakalokos].

We can understand this game better when we look at the last word, because it has different kinds of syllables in it. The first syllable has no onset, but does have a coda, while the last syllable’s nucleus is a diphthong.

When we apply the game rules to the first syllable, unlike all other examples, the reduplication process doesn’t simply copy the vowel:

From this we learn that the /ә/ was a surface representation of /ε/, but because the syllable ends with the coda /r/ a weight is applied to the vowel and it becomes influenced by something called ‘r-coloring.’ So, when we took away the r-coloring weight through prosodic circumscription the vowel reverts back to its underlying representation. When the previously circumscribed /r/ is added to the end of the new syllable the new /ε/ undergoes r-coloring and changes to /ә/.

When we apply the game rules to the last syllable of the last word nothing unique happens despite the syllable’s diphthong:

So from [әrχәtai] we get the new word [εkәrχәkәtaikai].

The Turkish language game, Ķus Dili, actually uses the exact same rules; however, instead of a /k/ being the consonant in the onset of the added syllable a /g/ is present instead. Kabak, supra, at 15. So, the Turkish word ‘renkli‘ [reŋkli] or ‘colorful’ would have this syllable structure:

When the rules of Ķus Dili are applied, which are the nearly the same as Korakistika’s, the following word, [regeŋkligi] is formed. Id. at 16.

So one of the games is just a replica of the other. There is only one thing distinguishing the two games, and that is while Turkish’s game uses a voiced /g/ Greek uses an unvoiced /k/. Voicing just means that the vocal cords vibrate when pronouncing the sound; otherwise linguistically a /g/ is the same thing as a /k/.

So now it looks like one language must have incorporated the game wholesale with only a voicing change taking place during the swap. Here is the cool thing about linguistics: I don’t have to open a history book to hypothesize that Greek got the language game from Turkish. In linguistics there’s something called Universal Grammar. This theory says that all natural human languages have some certain features simply by way of “genetic endowment.” Michael Kenstowicz, Phonology in Generative Grammar, (Blackwell Publishers 1994), p. 62. One of the features of Universal Grammar is a preference toward unvoiced consonants — “unmarked values appear in all grammars.” Id. at 62. Also, “the unmarked values are the first to emerge in language acquisition and the last to disappear in language deficits.” Id. Given this preference toward unvoiced consonants in the Universal Grammar theory, it is very unlikely that as one language swapped the game to another a previously unmarked consonantal rule became a marked one: or /k/ to /g/. Actually we would expect the contrary, that the game survived the stress of transferring to another language but in the process some grammatical rules reverted to the Universal Grammar. That is that the voiced consonantal rules reverted to unvoiced ones: /g/ to /k/. So Turkish transferred the game to Greek and in the process Greek reverted toward Universal Grammar and dropped the voiced consonant rule.

The most likely time period for Greek to absorb the game from Turkish would be during the Tourkokratia. Nicholas Ostler, Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World (New York 2005), p. 263. However, a native Greek speaker and scholar of Greek history was able to tell me confidently that Korakistika dates back to the Byzantine era. Maybe Greek speakers had contact with Turks before the Tourkokratia and the Greeks imported the game then.

Pingback: ancientworldtour